Cockburn Association: Edinburgh – The Prosperous City

Edinburgh heritage body the Cockburn Association has launched a series of thought-pieces under the heading Our Unique City: Our Past, Our City, Our Future to generate a civic conversation that looks to address the many challenges facing the capital now and in the immediate future.

Paper Two – A Prosperous and Equitable City – outlines issues in carbon reduction and economic expansion in the face of inequality and a speculative land economy.

Background

Edinburgh’s knowledge-based economy, together with strengths in tourism and the presence of the Scottish government mean that the city scores well on many economic indicators. Financial services and insurance, a long-established sector, employs 33,000 in the city. Almost 64% of the city’s workforce who are in jobs have at least a degree level qualification; this is a higher proportion than any other UK city. Over 38,000 people work in Edinburgh’s digital economy. Edinburgh has the lowest unemployment rate of any major UK city, and much of the 10% growth in jobs since 2012 was made possible by inward migration. Because it is home to high paying sectors, it is an affluent city, even by European standards. Yet there are still almost 80,000 residents living on incomes below the UK poverty level, and in several wards poverty rates exceed 25%.

Edinburgh’s Economic Strategy (2018) seeks to “enable good growth”. The Strategy is built around the aims of innovation and inclusion, and makes reference to listening to communities. It says that delivery of the strategy depends on strong collaboration between “anchor institutions that guide development of the city”. Over the past decade, a number of high profile developments have been promoted notably through The Edinburgh 12 initiative, on the basis that they will bring “jobs and growth”. Other planning considerations and the voices of civil society are given less weight. The new Economic Strategy and consultation on the forthcoming Local Development Plan provide an opportunity for more balanced decisions about future development.

Transition to a low carbon economy

The necessary transition to a low carbon economy needs to be grasped as an opportunity to improve quality of life for our citizens and to strengthen the local economy. The city council has been working with the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency and is expected to produce proposals for Low Emission Zones (LEZs) in May 2019. However, the City has set a target of a 42% reduction of carbon emissions by 2020. Given that walking represents 40% of all journeys to work in the city centre (18% city-wide), this suggests that the current levels of pollution are being imported into the city rather than derived directly from the current population. How can the City 2030 Plan support LEZs by reducing commuting from outside the city and cross-town commuting. Are measures such as applying enhanced emission standards to vehicles owned by residents the right way to tackle this?

Decarbonising the housing stock is important in Edinburgh, where almost half the houses were built before 1945, and two-thirds of accommodation is in flats, most of which are in mixed-tenure blocks. Improved energy efficiency in houses will also reduce fuel poverty, which affects 24% of Edinburgh households, reduce the flow of money out of the local economy to energy companies, and create local economic activity. However, it is accepted that much of the historic stock comprises listed buildings or buildings in Conservation Areas, which presents limited opportunities for significant interventions. They also represent a huge pool of embodied energy capable of adaptive repair and renovation. Given the importance of heritage to the city’s economy, pragmatic and proportionate approaches to addressing these properties will be needed. What policy initiatives can be developed to help manage fuel poverty in residential properties?

Edinburgh’s City Housing Strategy was updated in 2018. It says that council-led housebuilding will favour brownfield sites and have high energy efficiency. There will also be investment in existing homes to increase energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions. However, the strategy is strongly focused on the social rented sector, which, whil every important, is not the main source of new housing. Might new housing developments be required to support district heating schemes? Should every new housing development not include renewable energy technology built it, such as all roofs required to have solar panels (as was done recently in California, USA)? Continental cities that have led the way in low carbon design have set ambitious standards for new development. Are there areas of the city where community-based renewable energy companies might be set up, with revenues reinvested locally? Also, could new area-based initiatives deliver building maintenance and carbon reduction in the way that Housing Action Areas tackled modernisation in the 1970s? How can City Plan 2030 contribute to energy efficiency in homes and reduction of fuel poverty? What new policy mechanisms are needed to ensure new development builds renewable technology into the fabric from the outset? Could a modern equivalent of an HHA be created to help facilitate change?

Zero Waste Scotland has worked with the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce to identify business opportunities through a move towards a circular economy in Edinburgh. Particular potential has been identified in the events and festivals sectors; in facilities/buildings management; ICT and data infrastructure; and by-products from the production of alcohol. How might City Plan 2030 support the growth of a circular economy?

Spatial inequality –helping all citizens to benefit

The Community Empowerment Act and the Socio-Economic Duty both put reduction of inequality at the heart of public policy decision-making in Scotland. These requirements should be central to City Plan 2030, especially as disposal of major public assets at Astley Ainslie and at Redford Barracks will happen. The draft Planning Bill before the Scottish Parliament proposes the introduction of Local Neighbourhood Plans, enabling communities to come together to articulate their vision for their locale. How these might work in practice is unknown, but it could provide a bottom-up policy framework to guide city development. How can City Plan 2030 shape the future use of these extensive sites in a manner consistent with local needs and ambitions? To what extent should community interest dictate city policies?

There are several dimensions to spatial inequality, most notably linked to class, gender, ethnicity and disability, which can be intertwined. There are also examples of good practice internationally of how user-involvement in the plan-making process can lead to more equitable outcomes. How can the preparation and content of City Plan 2030 deliver a more equitable Edinburgh?

Local food networks

There is a growing market for local products, particularly in food. Not only does this reduce food-miles in long supply chains, but it carries the appeal of authenticity. This can add value to the tourist experience for example, and hotels and restaurants are responding accordingly. There is at least one city centre hotel that serves guests breakfast honey from hives located on its roof. In Belgium, a supermarket has created a vegetable garden on its roof, selling produce in the shop and using waste heat from its environmental systems to support growing. In addition, allotments remain much sought after in the city and, if protected or increased in numbers, have the potential to feed into local supply chains. Could pop-up community gardens be supported on vacant and under-used sites? What policy initiatives could be established to drive local food production?

Infrastructure

Leith Docks were constructed by the city to further its economic agenda. They were paid for by a penny tax on ale, using existing commercial activities to cross-subsidise development. Today, planning agreements are used to help fund public infrastructure. However, this does not cover all the costs involved, and depends on development taking place to release funds. This development imposes its own demands on infrastructure, with existing communities seldom experiencing directly the benefits but enjoying the impact in terms of increased congestion, longer queues at the GP surgery, etc. Should all infrastructure costs of development be borne by the developer (and landowner). Should the enhanced value of land created through a planning consent be captured fund infrastructure improvements?

Connectivity matters for prosperity and equity, both within the city and its region and to places beyond. These matters are dealt with more fully in a separate paper. Now that a decision has been taken to extend the trams to Leith and Newhaven, perhaps the main issues are about how to capitalise upon, and equitably share the benefits of development opportunities created by the extension?

Innovation and start-ups

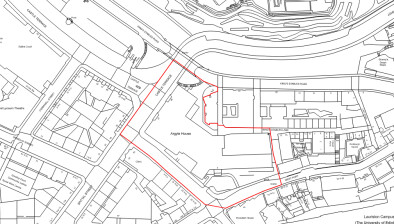

There is a risk that strong demand for commercial property, combined with its ownership by investors, will push up rentals and that this will restrict access to the kind of cheap, easy-in/easy-out premises that are so essential for business start-ups. Similarly, a key feature of the changing economy has been the proliferation of social enterprises, which again are likely to require cheap and accessible floorspace. Edinburgh has seen some successful innovative reuse of redundant buildings to provide clusters for nascent businesses, for example at Argyle House and at Summerhall. Where are the opportunities to replicate such models and what planning policies are needed to facilitate them? What policies are needed to facilitate this?

A smart, data-driven city

Data-driven technologies are likely to impact on most, if not all, of the above concerns. If the local development plan is to be robust to and beyond 2030 it needs to be aware of the likely impacts of smart city technologies, and set a framework through which the new technologies serve the public interest and remain accountable. Like many other cities, Edinburgh was blindsided by the rapid emergence and growth of short-term letting through platform businesses, and lessons should be learned from that. In addition, there are great opportunities to use emergent technologies to bring citizens closer to decision-making, and to make data about the city available to them.

Summary and the way ahead

Edinburgh is a prosperous city but that prosperity has not been shared equitably within the city. Some of the factors consigning so many Edinburgh households to poverty and to fuel poverty relate to macro-economic trends and public policy levers at levels beyond the local. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis the city prioritised “jobs and growth” without sufficient concern for the quality of that growth or for who were the beneficiaries. The 2018 Economic Strategy was therefore welcome in putting issues such as carbon reduction and redress of spatial inequalities on the agenda, not as barriers to the economy but as opportunities. In contrast, such concerns have been marginal in planning policy nationally and locally, with the system being framed to deliver on the aspirations of the property development industry. City Plan 2030 presents Edinburgh with an opportunity to plan for a city that is both prosperous and equitable: what ideas and evidence are needed to make that possibility a reality?

To access the full report, click here.