John Gilbert Architects: Thoughts on listing the Kingston Bridge

In response to Historic Environment Scotland’s proposal to list the M8 Kingston Bridge, John Gilbert Architects has published its thoughts.

It is irrefutable that the construction of the M8 motorway is of major historical importance to the City of Glasgow. Vast swathes of the city were cleared to make way for the wider motorway network, which includes the Kingston Bridge, and the fabric of the city was irreversibly altered as a result of this. Internationally, it is a rare example of a motorway taking pride of place in a city centre. Its presence is a reminder of the post war ideals of progress, individual transportation and suburban expansion.

However, the intervening 50 years have provided evidence that some post-war ideals were misguided. The rise of suburbia and personal transportation are widely accepted to have diminished the urban environment of cities around the globe, many of whom are now seeking to mend the scars left behind by the rise of the urban motorway. Yet instead in Scotland we seem to be seeking to preserve and protect them.

The fact that the Kingston Bridge carries more that 150,000 vehicles a day is not an engineering feat to be celebrated, but bad infrastructure planning that requires correction. Formerly a compact city, the Glasgow conurbation is now dispersed over a large area of west central Scotland. The dispersed nature of the city leads to thousands of cars entering and leaving the city each day. This is not only out of step with the solutions required to solve the climate emergency, it also damages the health of Glaswegians through air pollution. In this context, it seems inopportune to list the Kingston Bridge with the wider purpose to ‘represent the wider engineering achievement of the M8 motorway scheme.’

It can be debated whether the design of the Kingston Bridge has any specific architectural merit or represents an engineering achievement. However, it is reasonable to state that the Kingston Bridge is not internationally renowned like its Scottish contemporaries. It does not define Glasgow like The Forth Rail Bridge defines Edinburgh, or the Brooklyn Bridge defines New York, or the Golden Gate Bridge defines San Francisco. In fact it is the Clyde Arc that is most commonly used to project the distinctive image of Glasgow to the world.

It seems tenuous to suggest the bridge would have any meaning or merit without the wider infrastructure scheme, indeed it was this wider scheme that had an international influence rather than the bridge itself. From a perspective of historical understanding it would be uncontentious to say that the bridge could be replaced with another without diminishing the reading of the overall M8 infrastructure.

It can also be debated whether the planning of the bridge was a success. The bridge was intended to last 120 years but design flaws have necessitated expensive repairs in recent decades, arguably one of the most noteworthy things about it is that the scale of the repairs required to make the bridge fit for purpose made it into the Guinness Book of World Records. More broadly, parts of the infrastructure surrounding the bridge were only completed within the last decade. For over 40 years, the area was defined by ‘roads to nowhere’, visual evidence of the fact that the full plans for the ‘inner ring road’ were not completed due to widespread opposition from an alienated public.

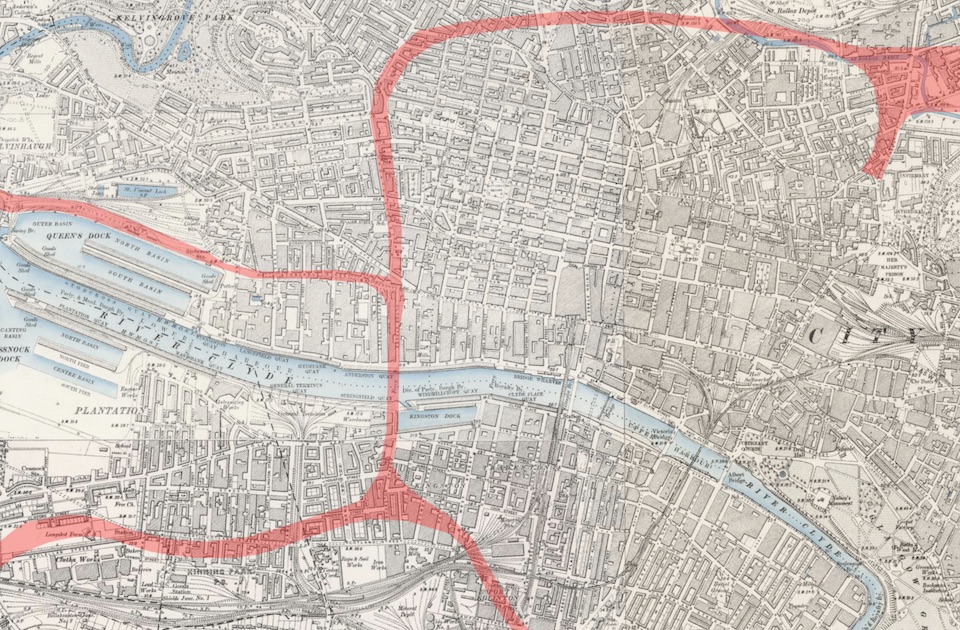

Thankfully today’s Glasgwegians don’t need to become acquainted with High Street, Speirs Wharf or Glasgow Green through black and white photographs. The same cannot be said of the areas adjacent to the M8 infrastructure, with the low uptake of land for development a clear indication of the key failing of the project: it is not compatible with a vibrant urban environment, community or any activities other than driving. Crucially, listing the bridge would appear to be culturally tone deaf to communities that were reduced to aggregate in Anderston, Kingston, Plantation, Cowcaddens & Townhead. Many of whom are still alive, many of whom have never found the same sense of community they experienced in ‘slum housing’. There will never be a lament with the line ‘M8 no more’.

Specifically because of its city centre location, listing the Kingston Bridge is incongruous with the prevailing consensus that urban motorways of the post war period were a mistake. Cities across the world are working to repair the damage to their fabric through downgrading motorway infrastructure, increasing density and promoting active travel and pedestrianisation more similar to Glasgow of 1940. Limiting the potential of urban renewal and repair around the Kingston Bridge risks perpetuating the mistakes of the past at the expense of the future.

This article was originally published on the John Gilbert Architects website.

The live Historic Environment Scotland consultation is available here.