Plan to turn one of Europe’s deepest mines into gravity energy store

Pyhäsalmi Mine

A small town in central Finland that is home to one of Europe’s deepest mines could host the continent’s first full-scale gravity energy store.

The community of Pyhäjärvi, with just 5000 inhabitants, lies 450 km north of Finland’s capital, Helsinki. Nearby lies Pyhäsalmi Mine – Europe’s deepest zinc and copper mine – owned by First Quantum Minerals, a Canadian mining corporation, and descending 1,444 metres into the earth.

Many of the mine’s operations have now ended.

However, a plan to transform a disused shaft into an underground energy store – using technology developed by Edinburgh energy storage firm Gravitricity – could offer new opportunities for the remote community.

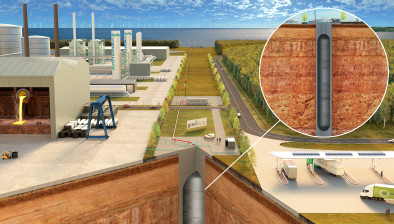

Gravitricity has developed a unique energy storage system, known as GraviStore, which raises and lowers heavy weights in underground shafts – to offer some of the best characteristics of lithium-ion batteries and pumped hydro storage.

The local community has set up a special development company, called Callio Pyhäjärvi, to promote regeneration projects at the historic mine, of which the GraviStore scheme will be part.

The two organisations have now signed an agreement to transform a 530-metre deep auxiliary shaft into a full-scale prototype of Gravitricity’s technology – and anticipate this could become Europe’s first GraviStore deployment.

They will now work together to develop the scheme – which would deliver up to 2MW of storage capacity. This would tie straight into the local electricity grid and provide balancing services to the Finnish network.

Last year, Gravitricity signed an agreement with Swedish-Swiss energy multinational ABB to use ABB’s mine hoist expertise to help accelerate the adoption of underground energy storage. It is anticipated ABB would lend its expertise to the project, alongside Gravitricity’s other strategic partner, Dutch winch specialists Huisman.

Gravitricity’s executive chairman Martin Wright said: “This project will demonstrate at full scale how our technology can offer reliable long life energy storage that can capture and store energy during periods of low demand and release it rapidly when required.

“This full-scale project will provide a pathway to other commercial projects and allow our solution to be embedded into mine decommissioning activities, offering a potential future for mines approaching the end of their original service life.

“It will also provide vital new low carbon jobs in an area which has suffered significantly from the end of traditional mining operations.”

During sixty years of operation, more than 60 million tons of ore were mined and more than 30 million tons of concentrates were produced. The mine paid more than 200 million euros in community tax during the decade before its closure, of which the town of Pyhäjärvi received a quarter.

The underground energy store would be one of a number of initiatives at the former Finnish mine, where Callio has been established by the local community and mine owners to kick start new projects at the mine including solar farms, new technology startups, mining technology testing facilities and an underground 5G network.

Callio Pyhäjärvi’s CEO Henrik Kiviniemi (Pyhäsalmen Kvanttikiinteistöt Ltd) said: “We can take advantage of the best of the region’s electricity grid and transformation of the energy market. It is also very attractive to take advantage of these opportunities for energy-intensive industry to be located here utilizing also the good logistical location of Pyhäjärvi.

“Our industrial park can provide an excellent framework for electricity-intensive operators in the future, like Gravitricity, who can utilize the infrastructure and local know-how coming vacant from mining operations.”

The mine’s underground copper and zinc resources were depleted in 2022 and mining ended in August 2022. Every day, close to 220 people worked at the mine, 70 of whom worked underground. Pyhäsalmi mine was the area’s biggest employer, and its closure led to a loss of a further 400 subcontractor and service jobs.

Since then, many of these people have found new jobs in other industries, or workplaces outside of the town or have started their own business or commenced studies for a different career.